GETTING ETHIOPIA DEAD WRONG

UPDATE: This 50,000-word version from Sept 2023 has now been updated in an 85,000-word version from August 2024, available in print and as ebook on Amazon: https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0DBTH3H3M/

They rank among the great and the good of our media, academia, humanitarian work, politics and diplomacy. Yet they demonized a friendly people and fueled a big war with dire mispredictions and shocking lies. Who were they? How could they get away with it? What was the full picture that they so distorted? And why?

“There is no military solution,” Western diplomacy droned on. But a military solution was exactly what Ethiopia sought when, in October 2022, its army pushed back into Tigray, the northern region where an insurrection had begun and expanded out from, some two years and countless lives earlier. Half-way into the fratricidal war, the rebels had even closed in on the capital city and were hailed in the world press as the imminent victors. Now Ethiopians became cautiously optimistic that the federal government would finally prevail with a prospect of stability.

However, across the world, this sigh of relief was drowned out by alarm bells ringing.

UN Chief António Guterres said on October 17 that the war was “spiraling out of control”. A senior Africa expert with an illustrious resume, Cameron Hudson, speculated out loud that the hundreds of thousands of people in the newly taken Tigrayan city of Shire might be about to be put to death. A tale of kill quotas with limbs and skulls on display graced newspaper columns. Do-gooders cried out for foreign intervention.

By now, global audiences had been primed for the slaughter of the six million or so inhabitants of Tigray. A natural authority on this subject, The Holocaust Museum, weighed in on October 25, announcing a “heightened risk of genocide”.

This echoed rebel leader Debretsion Gebremichael, who, the day before, had delivered a doom-laden speech to his comrades: “Their plan is not to administer or enforce the law on us. (…) It is to wipe the people of Tigray off the face of the earth. (…) The only option we have, so that we may not be annihilated, is to fully resist.” His chief general, Tsadkan Gebretensae, at the behest of the American Heritage Foundation, had just said: “Their desire is not only to dominate and control Tigray, but to exterminate the population.”

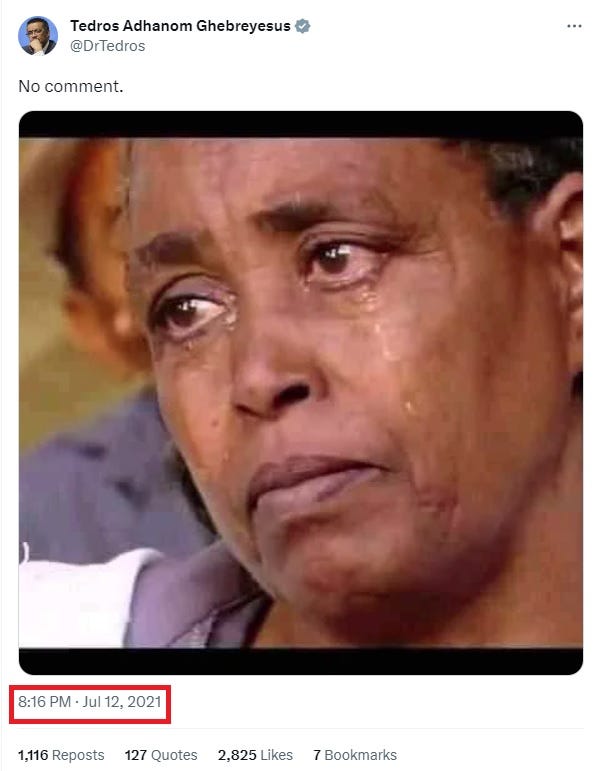

On a calmer note, The Ethiopian Government Communication Service released a statement saying fighting in urban areas had been avoided in order to spare civilians. Now the task was to coordinate relief aid and restore public services. Not a flicker of attention was given to such reassurances in international media. Their preferred Ethiopian source was Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, the Director-General of the World Health Organization (WHO). He had often anguished about the fate of his relatives in Tigray, and on October 19, he warned of a “very narrow window left to prevent genocide”. On October 30, he tweeted about “Ethiopian soldiers torching an entire town in Tigray”, illustrated with a shaky video. A frame-by-frame examination showed up nothing more than a bonfire at a safe distance from a house. Nonetheless, when Dr. Tedros speaks, the world listens.

World’s doctor or local warlord?

Notwithstanding criticism over his handling of the Covid pandemic, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus has recently built an image in the West as a donor darling. His initial hiccup of appointing Robert Mugabe as a WHO Goodwill Ambassador is long forgotten, as is how he picked a fight with Taiwan to ingratiate himself with Beijing. Since the war began in Ethiopia in November 2020, he has blended in among liberal democrats and accrued a shining halo, as he professes that “peace is the only solution”, flashes Greta Thunberg’s book, and spends MLK Day “reflecting on the interconnections between love, trust, peace and justice”. He is showered with accolades, from an honorary degree in Scotland to a $50,000 prize in the US. Dr. Tedros is not a medical doctor, but holds a PhD in Community Health, so The New York Times calls him “the world’s doctor”, portraying him as a stoic victim who towers above the dysfunctional politics of his country of origin.

But there he is seen as a chief instigator of the war, whose own children go to Western universities, while he sends the young in Tigray to kill and die for him and his clique. His job description of caring for global health is considered a mere smokescreen for his real vocation as a local warlord. Even his most innocent-sounding platitudes are read as coded messages to egg on the bloodshed.

Around the globe, many interpreted this cryptic Tedros tweet as an appeal for compassion. But in Ethiopia, it was heard as a cry for war. It came out on the exact same day that the WHO Director-General’s ethnically-exclusive party launched what was to become a march on the capital with the declared aim of overthrowing the multiethnic coalition in government. The offensive was codenamed: Operation Mothers of Tigray.

These contrasting views of the same man illustrate the theme of this paper, which is the even wider gap in the understanding of the war. The fact that Ethiopians have known Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus much longer and better than Westerners also foreshadows a broader point.

Dr. Tedros hails from the inner circle of Ethiopia’s dictatorial old guard, the Tigray People’s Liberation Front, TPLF. From 1991 to 2018, this highly disciplined party, with Marxist-Leninist-Stalinist roots, ran the country’s military, dominated its governance and held sway in its economy, despite Tigrayans making up only about 6% of the population. Many an Africa reporter has jumped to the conclusion that those 27 years of authoritarian rule by Tigrayan elites drove Ethiopians into genocidal rage against the entire Tigrayan people.

Identity politics is a big deal in Ethiopia, as it is in many countries. A picture-perfect of interethnic and interreligious harmony presents itself in the day-to-day of neighborliness, business, friendship, even in marriage and kinship. But chauvinism is a powerful political tool. Anti-Tigrayan revanchism is one of many extremist minority currents, but it was far from the driving force, let alone the root cause, of this war.

Diverging from the single story about Africa

The foreign correspondent struggles to convey a context unfamiliar to the audience in brief dispatches. It saves words to build upon the widely-known elements of “the single story about Africa” that the Nigerian author Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie has warned against. There is also a huge cultural meme on Ethiopia and man-made famine that is easy to tap into. And parallels to the Rwandan genocide are much catchier than explaining the complexities of Ethiopian affairs.

However lightly sourced, a quick fix of horror is intensely emotional. This longread also aims to be moving, but on the basis of patient insight. Part 1 goes through the predictions and mispredictions that revealed so much about correct and incorrect models of Ethiopian reality. Part 2 examines the widely-overlooked history that led to the conflict. Then Part 3 exposes some eye-popping contrasts between the claims and the evidence, between the high repute of the communication channels and the lowliness of the slander. Finally, Part 4 analyzes the incentives behind getting Ethiopia dead wrong. Without denying, trivializing, let alone justifying, any of the crimes that were indeed committed on both sides in the course of this brutal war, the conclusion is as scandalous as this: The media-borne narrative that Ethiopia’s motivation was to commit genocide was concocted to confer legitimacy on the violent pursuit of power.

This was always obvious to the majority of Ethiopians, and to foreigners like me, with longstanding immersion into Ethiopian society. What we said all along has today been confirmed, namely that the federal forces’ victory was not a recipe for genocide, but the only realistic path to peace. By standing in its way, Western powers caused immense damage to Ethiopia and to democracy worldwide, as pointed out by the largely ignored scholars who did get Ethiopia right.

I tried to get the message through as well, although newspapers that had previously published me and recognized my Ethiopia expertise could not let me write for them on this war. They would have come under accusations of propagandizing for the most heinous acts, without the background and confidence to argue back. Thus, however right I was on Ethiopia, I totally misjudged the West. I assumed that my own cultural realm, the world’s strongest democracies and our free press, would, by and large, have the back of an elected government against an authoritarian aggressor. This overestimated the power of context analysis and underestimated the single story about Africa.

The facts are appalling enough without exaggeration. Genocide became an activist mantra and a media buzzword, but failed to become an official designation. And, in fairness, the most knowledgeable diplomats privately shared our perspective and worked behind the scenes to soften the betrayal of Ethiopia. After all, TPLF supporters are also angry with the international community. Sending arms to the rebels was something proposed only by the craziest of crazy journalists. And yet, the politician braving the cries of “genocide denial” was a rarity.

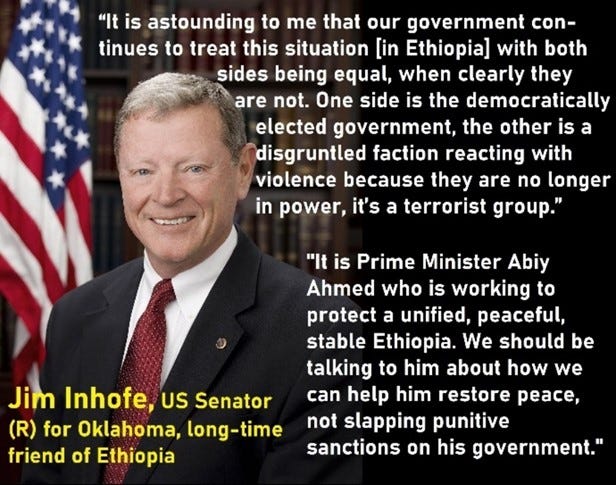

Spoken on the US Senate floor on May 27, 2021 by one of the most conservative members of Congress. Though there has been no clearcut left-right divide on Ethiopia policy, the accusations of genocide have mostly come from center-left people, who often staff media corporations and international organizations.

A paralyzing fear of standing with Ethiopia was instilled by big media trumpeting the stereotype of dark-continent savagery. Supposedly serious organizations favored anonymous witnesses over forensics. Body-snatching hyenas were repeatedly conjured up. Into this sensationalist slipstream jumped a string of noble-cause-hunting public figures with vivid ideas but little knowledge about Ethiopia. Many of them may have been well-meaning and deceived by disinformation that played skillfully to their prejudices. I have a naïve dream that just one of them will be moved by this paper to apologize.

When Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie spoke about the danger of the single story about Africa, I assumed it was the danger to non-Africans of not understanding Africa. Today I realize that, to the Africans who are not understood, this danger is deadly. Luminaries in rich and powerful countries poured obscene amounts of fuel on the fire. Their demonization of Ethiopians was less about Ethiopians than about self-projection. They pontificated about peace, while passing off the alternative to war as extermination. They waxed indignant about hate speech, while saying the enemy is a genocidal rapist. They preached international humanitarian law, while conniving with the recruitment of child soldiers. They fancied themselves as championing minority grievances, while siding with extremist ethnonationalism. They radiated charitable zeal, while pushing for the misery of some of the poorest people in the world. There are an inordinate number of such opinion formers who abused their establishment position and moral authority for a rotten cause, even more than the many who will be named and shamed here. Above all, lazy journalists took their cues from a handful of openly pro-TPLF academics and UN high-ups, who were elevated to neutral experts, even to moral arbiters, and whose disgrace, nothing less, this paper aspires to bring about.

Despite the heartbreaking sacrifices borne by her children, strong and single-minded Mother Ethiopia survived this attempt at her life. She has become warier, but remains friendly. It is high time to respect her and make amends. One way is to give aid. Even better are trade and investment. But most important is understanding.

CONTENTS:

INTRODUCTION ABOVE: GETTING ETHIOPIA DEAD WRONG

PART 1: PREDICTIONS AND MISPREDICTIONS ABOUT THE WAR

PART 3: NARRATIVE ABOUT THE WAR

PART 4: LESSONS ABOUT OURSELVES FROM THE WAR

An Ethiopian photo collage associates Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus with the TPLF troops' destruction of health facilities in Amhara and Afar Region. The WHO Director-General would only ever talk about violations of international humanitarian law in the Tigray Region.

PART 1: PREDICTIONS AND MISPREDICTIONS ABOUT THE WAR

A death wish foretold

“Why Ethiopia is spiraling out of control” was explained by the English academic Alex de Waal for the BBC and others in gloomy terms, when war broke out in the northern region of Tigray in November 2020. He scolded the Trump Administration for “indulging” the Ethiopian leadership, and pleaded for Biden, the incoming president-elect, to take a tougher line. During the two terrible years that followed, Alex de Waal became perhaps the most prominent Ethiopia pundit worldwide. He was a fixture in media big and small by November 2021, when the advances of the insurgent Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) caused him to wax lyrical, literally, as we shall soon see. However, by October 14, 2022, with all the fighting back where it began, he was again warning of “another genocidal onslaught on Tigray”. His conclusion was that, whatever the outcome of soldiery and diplomacy, Ethiopia was now doomed to become a failed state. He elaborated in a live interview two days later, saying that it had “essentially collapsed already”, while dismissing the African-Union-led peace negotiations as “a fraud” and “a sham”. This is when he finally admitted that the rebel army was being overrun. Yet he insisted that morale remained high, presaging a bloody showdown: “The Tigrayans have every motive to fight to the death”, he wrote.

And then, it turned out, they had more motive to live! Doomsday in Tigray was called off with the polar opposite of fighting to the death against a failed state, namely yielding to state monopoly on violence. Because this was the gist of the agreement announced in Pretoria, South Africa, on November 2, 2022, mediated by the African Union. The most salient provision was the disarmament and demobilization of the TPLF’s irregular army. This had long been Ethiopia’s declared war aim, but it had never been taken up by the international community. It was clearly enabled solely by the Ethiopian state prevailing militarily.

All the nations of the world rushed to praise this “African solution to an African problem”. The WHO Director-General, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, uncharacteristically, kept quiet. The day after, he put a brave face on it by retweeting a congratulatory message from the EU foreign-affairs supremo, Josep Borrell.

How could he not? Mr. Borrell had consistently backed Dr. Tedros’s views on the war. Only three weeks before, Mr. Borrell had even been acclaimed by the TPLF’s top negotiator and spokesperson, Getachew Reda. Recent appearances may deceive, as Dr. Tedros has been tweeting out mind-numbing pacifism and Getachew Reda a lot of military bravado. But these two are on the same team, and still profess brotherhood and mutual admiration. This goes back to 2012-2016, when they served together in the cabinet of Ethiopia’s central government. Both were renowned as hardliners against the pro-democracy protests.

Now Alex de Waal entered the fray again from his important BBC platform. He rained criticisms on the permanent settlement, calling it a mere truce. He stated candidly: “Tigrayans at home and in the diaspora have greeted the [peace] deal with dismay.” As per his custom, he equated Tigrayans with TPLF supporters.

While Tigrayans in the street expressed relief, they did indeed have cause for dismay too. The TPLF had accepted to lay down arms as a last resort to survive. This showed its leadership never really believed that the enemy had “genocidal intent”, as claimed by Getachew Reda just two days before signing. It raised the question: Why were so many sent to die for terms that could have been easily obtained without violence? Some two months earlier, on August 24, the TPLF had launched a second offensive outside of Tigray, right after rejecting negotiations. Getachew Reda had even penned an opinion piece headlined: “The African Union cannot deliver peace in Tigray”.

As a face-saving device, humanitarian access was touted as a concession to the TPLF. However, as military strategists know, making life bearable for the locals is key to countering a popular insurgency, which was the TPLF’s remaining card. We shall return to the crucial issue of what caused so much hardship in Tigray, as well as in the neighboring regions. The point here is: humanitarian access was never thought of as a concession by anybody in the Ethiopian camp, where celebrations of the peace agreement were tempered only by distrust of the TPLF’s readiness to comply.

By contrast, angry and bewildered TPLF activists in the diaspora, many of them children of ancien régime officials, protested by taking their cars to block a highway in Seattle and a bridge in Washington DC. Mr. de Waal speculated that “some Tigrayan commanders would rather continue guerrilla war than submit to what they regard as humiliating terms”.

Getting Ethiopia right

Senior officers on both sides of the war used to study under Professor Ann Fitz-Gerald, currently the Director of the Balsillie School of International Affairs. In 2004, she came to Ethiopia from a background in NATO to teach security governance and strategic planning for 15 years. This made her exceedingly well-versed in Ethiopian politics and military matters, talking to key actors on a daily basis. During the escalation process, she published specialist articles on the looming threat. When war broke out in November 2020, she too was pessimistic about a prompt resolution, but, by late August 2022, on the verge of the federal forces’ decisive ascendency, she expressed faith that the AU-led peace negotiations could soon succeed.

A few months earlier, in March-April 2022, she presented a survey titled “The frontline voices: Tigrayans speak on the realities of life under an insurgency regime”. It was based on visits to communities and IDP camps, interviewing 162 persons both individually and in focus groups. These were mainly civilians who had fled from Tigray into the Amhara Region, in addition to a smaller number of forced TPLF recruits who had been taken into safety at a camp in the Afar Region.

This treasure trove of heart-breaking as well as heart-warming personal stories led her to the opposite conclusion of Alex de Waal, namely that morale was sinking among the rebels, who were resorting to ever-harsher coercion to conscript their foot soldiers, including denial of food aid and imprisonment of family members. Many interviewees had run away because their name was on an arrest list, or for finding out about the fabrication of evidence for war crimes. Shortly after, a Tigrayan doctor, Aregawi Hagos, also escaped, telling the Ethiopian press about the TPLF’s misuse of humanitarian supplies and medicine, while lamenting that his family back in Tigray would be punished for his saying so. The TPLF’s increasingly draconian recruitment drive, described by Professor Fitz-Gerald’s informants, was later borne out by journalistic reports.

As Getachew Reda put it on November 7, justifying his acceptance of disarmament to disgruntled hardliners, many of them living in the West: “Our people (…) have suffered beyond what ordinary mortals can endure”.

Nobody could dispute the suffering. But throughout the war, Alex de Waal and like-minded analysts pointed to this suffering as the reason why Tigrayans had no choice but to keep fighting. Then, it turned out, they stopped fighting precisely to end the suffering.

Mr. de Waal can say, as he did, that an impending famine was what subdued the insurgency (a central allegation that will come under the microscope in Part 3). But he had insisted that Tigrayans would fight to the death, because the concession demanded of them was also death. The moment this was proved wrong, it pushed Mr. de Waal’s justification for running an irregular army onto much rougher terrain, on which he had consistently avoided treading, namely some unspecified “political claims”, in other words, the violent pursuit of power, which, as will be demonstrated in Part 2, is what this war was really about.

Struggling to accept peace

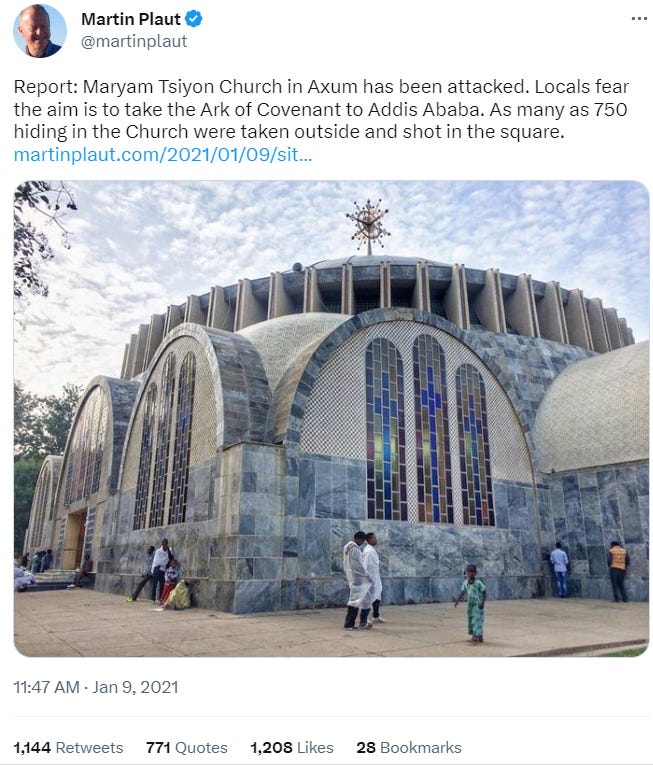

Martin Plaut is a well-connected former BBC Africa Chief Editor, still featured as a pundit on the BBC and elsewhere, just as he will reappear throughout this paper as a major shaper of the news agenda. He was a pioneer in predicting, as early as July 2021, that the rebel army’s march on the capital would be a walk in the park. On November 3, 2022, the day after the Pretoria Agreement, he was interviewed by Tigrai Media House. He portrayed this latest development as the TPLF leadership reckoning without the people of Tigray, who are “all those that could conceivably fight, [and] went to fight, because they knew the alternative was death, or worse”. Like Alex de Waal, Martin Plaut could not adjust so quickly to Tigrayans rather fancying their chances of living without walking into the killing fields. On November 8, he tweeted “worth a listen”, linking to an anonymous voice with a southern drawl. It called the peace deal “the extermination agreement”, suggesting that the TPLF’s negotiators in South Africa had signed under duress. It also claimed that clashes were still going on and could not be stopped. Martin Plaut would continue into 2023 to toy with the idea that the war was about to rekindle.

However, the TPLF seems to have exhausted its military means, practicing politics in more modest ways. On December 26, 2022, a federal-government delegation travelled to Tigray’s capital, Mekelle, where the TPLF’s number one, Debretsion Gebremichael, thanked his partner in peace, no longer a genocidal dictator, but “Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed with high regard”. Not long ago, Abiy Ahmed’s narrowly-missed top target for assassination was Getachew Reda. He, in turn, would call the prime minister a “child killer” who will “get it in the neck”. An appalling amount of dying later, the two met for a talk on February 3, 2023, albeit with stern faces, which relaxed into big smiles on April 24, when they shared the stage at a self-congratulatory peace ceremony in the capital, Addis Ababa. Foreign dignitaries present beamed over this new spirit of reconciliation.

Meanwhile, Ethiopians on both sides rolled their eyes. The TPLF’s supporters find it hard to stomach the embrace of their archvillain. And the TPLF’s detractors had expected the senior rebel leaders to be punished. The old guard’s continuing dominance of Tigrayan governance, with Getachew Reda named the interim regional president and Debretsion Gebremichael still heading the TPLF, also means the Tigrayan population stays under the party’s iron rule. Then again, this may be preferable to victor’s justice, which could well provoke a smoldering insurgency in Tigray.

On the other hand, the perception of indulgence towards the defeated side, aggravated by a series of other controversies, has dented the popularity of Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed Ali. It has even been a factor in opening up a rift with former allies from Amhara Region, which has recently taken a violent turn, frustrating the much-needed demilitarization of Ethiopian politics. The hope of building a democracy lives on, but the term ‘Abiymania’ today describes a closed chapter in history, to be revisited in Part 2. Finding one’s way around a complex society takes a good rearview mirror.

A remarkable Prediction Prize win

It is fair to judge analysts on the accuracy of their predictions (or their warnings of what will happen absent corrective action). The ability to see what comes next is the hallmark of a good model of reality. Conversely, mispredictions call for revising the model.

Digging into the past to check for the most detailed foresight, one analysis stands out, authored by the American Horn of Africa specialist, Bronwyn Bruton, as early as July 2018, when the world had just warmed to the fresh face of 41-year-old Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, installed three months earlier in the wake of years of popular protests. He had wasted no time in breaking with an oppressive past and embarking on liberalizing reforms. The freshly coined word ‘Abiymania’ was all the rage. There was exuberant optimism. Ms. Bruton begged to differ. I remember reading her in Foreign Policy at the time, finding her insightful, but overly alarmist. Tigray was uncooperative yet stable, unlike some other regions, where violent ethnic chauvinism was displacing millions. The grumpy old warhorses in Tigray looked like a dying breed and the least of Ethiopia’s many problems.

However, as it turned out, Ms. Bruton’s premonition of slowly-escalating tensions between the federal government and the Tigrayan regional government, with potential for full-blown civil war, was eerily prophetic. In making her case, she described the future causes of the war, which were later to be terribly misrepresented by lesser pundits. Her list was topped neither by ethnic animosity nor disputes over regional autonomy. The most immediate concern was that the new civilian authorities in Addis Ababa would be unable to control the army, a risk to peace that is as big as they come to a poorly consolidated regime. After all, the vast majority of senior officers were not only Tigrayan, but also staunch TPLF loyalists. She then correctly foresaw that the TPLF leadership would seek to retaliate for its loss of monopolistic economic power by activating its well-established and still well-funded patronage networks to whip up ethnic pogroms across the country.

She even foreshadowed Western cluelessness: “the White House and European leaders appear unaware of the life-or-death power struggle that is unfolding”. In the looming turn to violence, she cautioned against American bothsidesism, yet lamented that: “If history is any guide, however, Washington will prefer to hedge its bets.” She anticipated that the US would be “maintaining ties with the TPLF”, whose “shocking human rights abuses” had long been “blithely overlooked” due to reliance on its extensive security apparatus in the fight against radical Islamism in Somalia. On a final note, she warned that TPLF hardliners “may be desperate enough to act irrationally”, but would do well to notice “how many enemies they have”. Indeed, there was prescient advice in there for everyone.

In laying out the timeline for the next couple of years, only the Covid-induced election postponement caught Ms. Bruton unawares. After all, she was not a psychic, just a rock-solid connoisseur of Ethiopian politics and a razor-sharp analyst. Alas, there were to be more missed chances to listen to her and save lives.

With foreknowledge of what lasting peace was going to look like, this last warning was issued nine days into the war (when disarmament was not yet achievable through negotiation).

Bronwyn Bruton, Ann Fitz-Gerald and others kept contributing their expertise throughout the war. However, their view that the TPLF’s leaders were the main spoilers remained on the fringe. What was amplified the most was the judgment of those who got it consistently wrong. And not only about the peace. They were even further off the mark about the war.

Rebels at the gate, reportedly

The Norwegian Kjetil Tronvoll is a New York Times-quoted, The Guardian op-ed-writing, internationally sought-after Ethiopiologist, also presented as a neutral academic, even though, like Alex de Waal, he is not coy about his closeness to the TPLF hierarchy.

Kjetil Tronvoll is also a bit of a clairvoyant. For a long time, he has proudly pinned this on top of his Twitter profile, announcing the imminence of war.

We shall return to the information that this was based on, and what happened after this tweet.

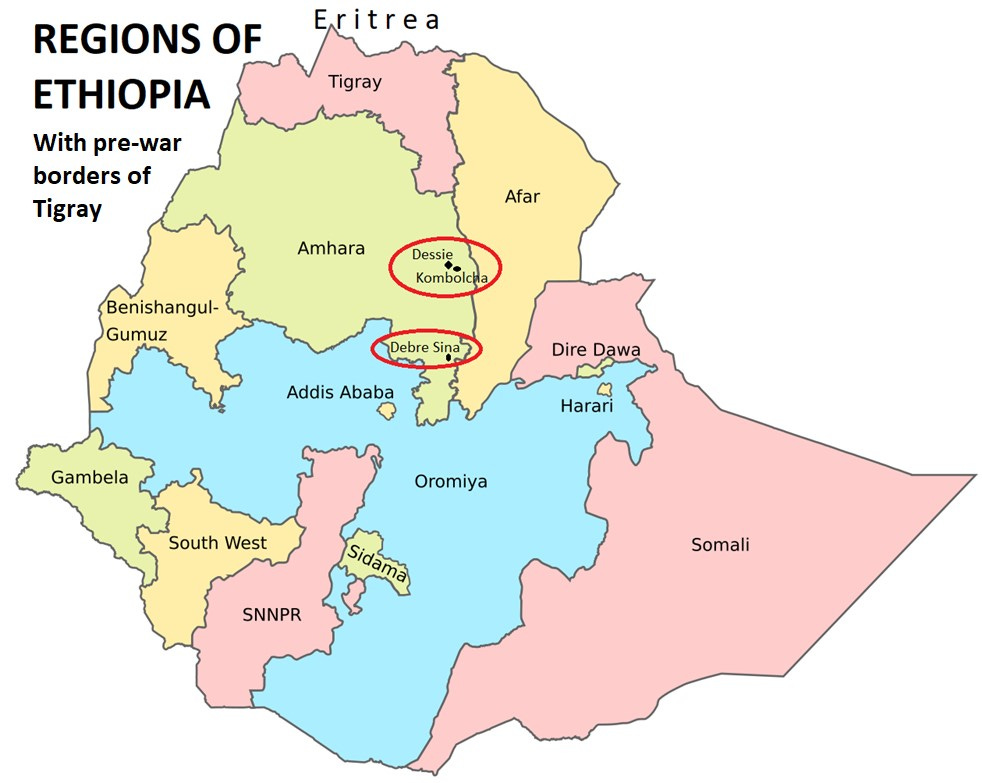

Fast forward to October 2021. The war has now been raging for nearly a year, moving from Tigray towards the east into Afar and towards the south into Amhara.

The astonishing advances of Operation Mothers of Tigray has Getachew Reda, chief TPLF spokesperson, referred to by Mr. Tronvoll as “my brother”, gushing with confidence in his troops.

The cities referred to lie about 400 km from Addis Ababa, and are taken ten days later. For over a month, the TPLF army keeps approaching the seat of government, until reaching Debre Sina, some 200 kilometers away, in the last week of November 2021.

The TPLF is not the only ethnic militia closing in on the center of power. On November 8, Jaal Marroo, commander of the Oromo Liberation Army, OLA, claims that his fighters are within 40 km and is confident of “victory very soon”. He reports that government soldiers of Oromo ethnicity are defecting en masse to his side, which, if true, means Ethiopia’s unitary state is doomed. After all, while Tigrayans are only 6%, Oromos are the most numerous ethnic group, making up about a third of the population. Oromo extremists like to say the real share is up to 60%, so as to make the case that Oromos, for all their success integrating into Ethiopia’s multiethnic mainstream, are still underrepresented, and that Oromos in senior positions are token collaborators.

However, while the TPLF of today has a long record of governing, building international networks, accumulating wealth in foreign currency, and communicating with skill and sophistication, the OLA comes across more like the TPLF in its infancy in the 1970s, that is, as a ragtag bunch that finances itself by robbing banks and kidnapping for ransom. The OLA is a recent splinter group from the Oromo Liberation Front, the OLF, which was in exile until 2018, when it accepted an invitation from the new Oromo prime minister to participate in the fledgling democratic framework. The OLA, also known as Shene, has by now built a reputation for massacring civilians, especially among the ethnic minorities who inhabit the vast, lush and otherwise diverse and welcoming Oromo Region, called Oromia.

At this decisive stage of the war, in October-November 2021, the pressing question about the OLA is this: Given its repulsive methods, its new-found alliance with the TPLF so shortly after Oromo protestors were at the forefront of dislodging the TPLF from power, and with an Oromo leading the country, flanked by numerous Oromo ministers and Oromo senior officers, does the OLA really enjoy much popular support among Oromos? Mr. Tronvoll believes that it does.

Ordinary Oromos are onboard with the OLA, Mr. Tronvoll assumes.

TDF: Tigray Defense Forces, the TPLF army. ENDF: Ethiopian National Defense Force.

At this point of the international press coverage, it has become a truism that tribal affiliation overrides loyalty to the multiethnic federal setup. Moreover, this comes hot on the heels of Kabul falling to the Taliban in Afghanistan on August 15, creating a sense of foreboding.

Another historical parallel is frequently brought up in the news. In 1991, the TPLF marched from Tigray to Addis Ababa to overthrow the Derg, the Soviet-aligned communist dictatorship under Colonel Mengistu Hailemariam. The big difference is that, in 1991, they were greeted as liberators, whereas this time, in 2021, fierce resistance is expected. The US State Department appeals to both parties for ceasefire and negotiations. Kjetil Tronvoll, having now accumulated 31 years of research to back up his analysis, will have none of it.

By comparison, the leader that The Economist publishes on November 4, 2021, is less cocksure of the outcome. It has the sensible headline: “Act now to avert a bloodbath in Ethiopia”. But then it trains all its verbal firepower precisely on those who are acting now to avert a bloodbath. Ethiopians’ ongoing mobilization to defend their capital is portrayed as a craze of persecution targeting the city’s numerous ethnic Tigrayans, incited by a leader who uses “dehumanizing language” about them. This is cause for alarm, if true, but both defamatory and inflammatory, if untrue, so Part 3 shall look carefully at this and other grave charges leveled by The Economist at this dangerous crossroads for Ethiopia.

Admitting to cluelessness as to how to avert a bloodbath, The Economist suggests “outside powers” applying “a determined mix of pressure and persuasion”, though it thinks those well-intentioned Westerners might find Abiy Ahmed difficult to even converse with, as he is “exuding a Messianic zeal”. This judgment is backed by an unnamed diplomat saying: “He can’t understand why the West is not supporting him in fighting the forces of darkness.”

But is it really so delusional to think that the West would support an elected leader with a liberal reform agenda against an armed assault by the dictatorial old guard? The answer turns out to be: yes, totally delusional! The Economist leader’s preferred source, labelled “diplomats”, also believes that the TPLF “may be holding back from an immediate attack on the capital so as to give Abiy a chance to give up and escape.”

The proverbial CNN fake news

On November 5, 2021, CNN, its website having two days earlier quoted an unnamed “senior diplomatic source” saying that the two rebel groups were on the outskirts of Addis Ababa, announces this as news on live television, though this time only for “Tigrayan troops”.

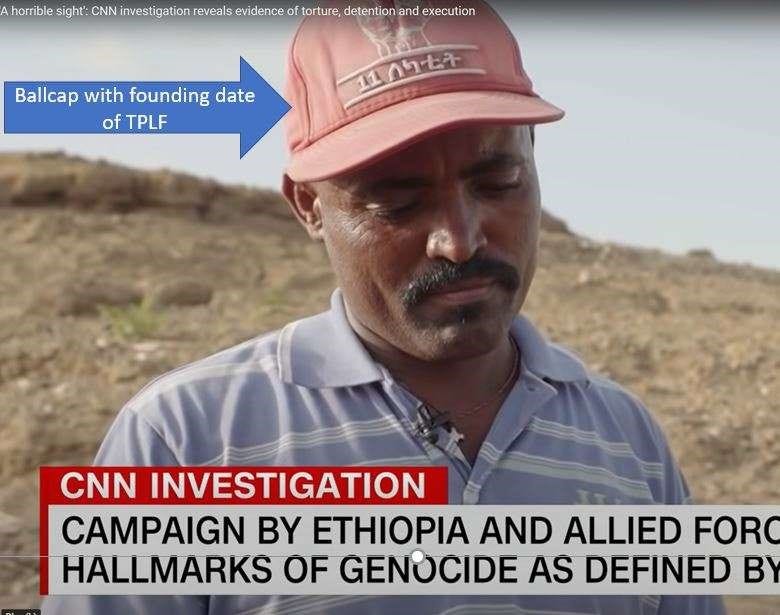

CNN’s shocker, using old and unrelated footage. Notice the use of “Tigrayan” rather than TPLF or Tigray Defense Forces (TDF). A consistent trait of CNN coverage has been to portray the conflict in crude tribal terms.

This provokes some anxiety. It would have induced all-out panic in a city of about six million inhabitants, had CNN not taken care to destroy its trustworthiness among Ethiopians over the previous two months.

First, on September 5, 2021, its star journalist Nima Elbagir had reported on dead bodies floating down the Tekeze River from Tigray into the Setit River in Sudan. This claimed “to reveal what appears to be a new phase of ethnic cleansing in Ethiopia’s war”. The corpses were presented as civilian Tigrayans killed by Ethiopian death squads for their ethnicity. However, intriguingly, a first version of the article (still available on the Wayback Machine) mentioned some experts affirming that all the corpses had been exposed to a chemical agent to preserve them after death. What could possibly explain this? No theory was presented, but it confirmed the suspicion voiced by Ethiopians that these were the TPLF’s war dead used to play a propaganda trick on the international media. Moreover, about ‘Gerri’, the Tigrayan inside Sudan who was featured as a key witness, the article said: “his community usually finds the exact number of bodies it has been told to expect”. This indicated coordination between the people dumping and collecting the bodies. Worse still for CNN’s credibility, on September 10, it discreetly edited out the crucial information about the chemicals. However, it admitted there had been an elaborate process to preserve the bodies lasting “at least three months”. This sat oddly with the article’s headline and its anonymous testimony, which suggested that the victims had been marched out of prison moments before floating down the river. And why would murderers go to such lengths to preserve the evidence, then dump it into an international river and let others downstream know with numerical precision what to pick up? Rather than attempting to make sense of it, Nima Elbagir stood by her blaming of Ethiopia and contextualized it as a genocide.

Incidentally, this is just a foretaste. Part 3 will present a whole pattern of shocking accusations that cannot be sustained, yet are just papered over by diverting the attention to new ones.

The primary CNN source for the floating-corpses story was Gebretensae Gebrekristos, or ‘Gerri’. He is seen in the interview video wearing a ballcap with the TPLF’s founding date and insignia. According to the Ethiopian diaspora site, abren.org, this shows he was a TPLF fixer. But his community was probably not supposed to reveal it knew exactly how many bodies to collect and when.

Nima Elbagir went on to attack Ethiopian Airlines, the national flagship carrier, which is a major source of foreign currency (incidentally with a Tigrayan CEO at the time). CNN had played dirty with this company before, coming after its safety record over a crash on March 10, 2019, which turned out to have been caused by Boeing’s defective software. Now the accusation was of transporting weapons, prompting the Biden administration to threaten more sanctions. Ethiopian Airlines denied it, and no charges were ever brought before an international entity, probably because, even if it did occur, it was not against aviation law. One year later, when CNN received an award for this story, Nima Elbagir would be heartily praised for all of her reporting by Getachew Reda.

It is now November 5, 2021, the day when CNN announces that rebels are at the gates of Ethiopia’s capital, the seat of the African Union. Up next should be chaotic scenes in the airport. Will there be people clinging to and falling off planes, as in Kabul? No, because most of the inhabitants of Addis Ababa shrug it off as just some more of the proverbial CNN fake news. And yet, for nearly a month, the pundits’ cliché continues to be that Addis Ababa is falling in “a matter of weeks if not days”. The rebels put it more modestly: “A matter of months, if not weeks”.

“Face your day of reckoning”

Also on November 5, 2021, a farcical spectacle is acted out in Washington DC, playing up the notion of oppressed Ethiopian ethnicities scrambling to join the TPLF-OLA victory parade. A massive press corps attends, as the leaders of seven more rebel armies sign on to join in the new nine-group coalition of ‘Revolutionary Front’ this and ‘Liberation Movement’ that.

In Ethiopia, nobody has ever heard of these outfits. Officials roll their eyes and call it “a publicity stunt”. It is indeed, and not a sophisticated one at that. But the world press laps it up and spreads it across the globe. No major news outlet cares to conduct any research into these entities, or to listen to Ethiopian researchers who easily dismiss their threat level. The story is good, and it is at least nominally true, even if giving it any importance is actually a deception. Worse still, no editorial finds fault with the capital of the free world hosting a pledge to snuff out an elected government with machineguns, artillery and tanks.

On November 10, Alex de Waal writes: “The Tigray Defense Force has comprehensively defeated the Ethiopian National Defense Force. Abiy has lost the war”. Little does he know that, less than a year later, when it is the TPLF that is on the verge of losing, he too shall resort to saying that “there’s no military solution”. Now it is November 16, 2021, as he live-streams an exultant victory address. It includes a short message to the presumably already toppled prime minister, quoting a poem about a dying despot, composed by Rudyard Kipling (somewhat inappropriately also the author of ‘White Man’s Burden’). Mr. de Waal asserts that Ethiopia is about to change into something radically different, perhaps “a commonwealth of independent states”. And with an austere expression, he rubs it into the faces of the vanquished: “Face your day of reckoning!”

Meanwhile, the approximately 15 million people in Amhara and Afar who live under TPLF occupation are suffering pandemonium. Already in August 2021, USAID Mission Director Sean Jones had stated that the TPLF loots food-aid warehouses wherever it takes territory outside of Tigray. There is no attempt to administer those areas, let alone win over the local population, but only to extract resources for the TPLF war machine. All equipment in hospitals and other health facilities, pharmacies, schools, universities, offices, factories, even waterworks, is plundered, and, if it cannot be transported to Tigray, it is destroyed. Rapes and executions are reported, though we also hear about TPLF child soldiers asking locals to hide them in order to defect. We get a foretaste of what to expect if Addis Ababa falls.

This is when Alex de Waal tells the TPLF army: “You have won the respect of everybody. The doctrine of a just war has rarely had so clear an exemplar.”

A few months later, when the regime change that he so jubilantly poetized has turned out to be a pipedream, Alex de Waal will strike a more somber note, always prefacing his interviews with “condolences” to the Tigrayan people. But had he cared for their lives as he did for the political goals of their leaders, he would not have said that they had “every motive to fight to the death” two weeks before a peace agreement, which he then poured scorn on.

Not feeling oppressed

I was in Addis Ababa when the city was being marched upon. I experienced none of the pessimism, chaos and disunity anonymously reported in The Guardian. On the contrary, it was a moment of urgent fraternization across every divide. People here have fresh memories of the TPLF-led regime and the sacrifices made to get rid of it. They were in no mood to let it back in. Even chubby, well-to-do family fathers vowed to pick up a gun if the enemy came to town.

Conducting politics along ethnic lines has been the hallmark of the TPLF, and on this occasion, it pinned its hope on driving a wedge between the two big ones, the Oromo and the Amhara, playing up Oromo grievances and appealing to Oromo revanchism. This tactic played not only on the questionable notion that the Amhara were once an oppressor people, but also on the dangerous falsehood that they are still so today. This kind of thinking does indeed have eerie echoes of the Rwandan genocide. But the TPLF and its new ally, the OLA, had to contend with the strong Oromo representation at the central level, starting with an Oromo prime minister.

The analyst Rashid Abdi has won the ear of The New York Times, the BBC, and CNN, among others, by presenting Ethiopian politics in crude tribal terms, casting the Amhara ethnic group as perennial oppressors who are also puppeteering the Oromo prime minister.

Here, he plays up Oromo victimhood and taunts Oromo leaders serving in the federal government as being “complicit”.

A few years back, when the self-same TPLF leaders held power in the federal government, they would accuse armed Oromo factions of being foreign-backed terrorists. However, alliances shift quickly and opportunistically in times of war. For its assault on the capital, the TPLF was looking to fellow violent ethnonationalists in order to expand its recruitment pool.

Stirring the pot, Mr. Tronvoll retweeted a video of unknown origin, showing mothers from an Oromo village weeping as their sons are carried away by bus, with an accompanying made-up story that they were being forcefully recruited for war by Abiy Ahmed.

In contrast to the total-war regime suffered by the population in Tigray, there was no conscription for the federal army. However, a maxim of the disinformation war was: Show any picture, make any claim. There has been no accountability for such blatant lies, not even for bigtime media pundits.

Declan Walsh of the New York Times, who, as we shall soon see, led the pack in forging the war narrative for mass consumption, also bought into the notion of age-old resentment of the Oromo masses, who would not be fobbed off with an Oromo prime minister.

The Oromo cause spans a wide spectrum. At one end, it promotes cultural pride as part of Ethiopia, chanting “peace and unity”. At the other, it warps a complex history of empire to wallow in victimhood, hankers after an ethnically homogenized, militaristic utopia, and rejects the multiethnic state as an Amhara or an Amhara-Tigrayan colonial project, even when Oromos play leading roles in it. There are many shades of Oromo ethnonationalism that lie in-between. But the big fault line here is not between Oromos and other Ethiopians. It is between Oromos cultivating their Oromo identity within and against the Ethiopian unitary state, without violence and with violence.

Recently, OLA terrorists have been getting frighteningly near multiethnic Addis Ababa, on which they make a tribal irredentist claim going back to before the capital was even founded. Though this conflict is not the topic of this paper, there are some applicable lessons from the vitriolic propaganda being cooked up to nurture it. It follows a recipe that brews hate from historical half-truths, is artificially flavored with the struggle of black Americans and spiked with collective guilt, so that, hey presto, it can be served up as intellectually respectable grievance to the taste of The Conversation, a Western mainstream magazine and Gates Foundation grantee. Such exotic yet lethal fare is also apt to become glorified by a former US ambassador, romanticized by the Swedish state broadcaster, hyped in an American fashion magazine, and poetized in The New Humanitarian. As this paper shall demonstrate in much more detail with the TPLF narrative, too many Westerners lap it up, because they find fulfilment in handing out medals at the African Oppression Olympics, even if all they have to go on is the artistic-impression score.

Oromos have a wide variety of religions and political views. But every single one of those that I have met, in my frequent visits to Oromia, is happy to mix and mingle with the many other ethnicities that live among them. They may lament how the Oromo language, Afaan Oromoo, is losing out in their towns and cities to the national lingua franca, the Amhara language, called Amharic, which they are nevertheless perfectly comfortable speaking and singing along to in their favorite pop music.

Oromia promotes itself, rightly, as the land of diverse beauty and multilingualism

The mainstream Oromo identity is among the most easy-going in the world. However, radical Oromos reserve their worst bile for pro-Ethiopian-unity Oromos, who are seen as either traitors or sheep.

While marching on Addis Ababa, the TPLF and its supporters were keen to exploit this rift by pandering to OLA ideology, and especially by promising the OLA and its might-be recruits that they would be rewarded with Ethiopia on a platter. Thus, in a podcast in Norwegian on November 12, 2021, Mr. Tronvoll reaffirmed the dubious talking point that, upon taking the capital, the TPLF would stay out of central government, whereas: “The Oromo people’s army, the OLA, they see Addis Ababa as Finfinnee. Finfinnee is the Oromo name for Addis Ababa. This was originally [over 130 years ago, ed.] an Oromo village, as it lies in the middle of the Oromo heartland. So the OLA is there to liberate Finfinnee, to liberate the Oromo capital, and take control of the Oromo capital, not as Addis Ababa, not as the capital of Ethiopia, but as Finfinnee, the capital of Oromia.” He expressed no concern about this ruthless gang imposing its angry ethnonationalism on a multiethnic megacity against the will of virtually all its inhabitants, including the 20% or so identifying as Oromo, most of whom would have been deemed ‘complicit’. He even echoed the extremist historical narrative, saying the Oromo people had suffered “black-on-black colonization”.

Generalizing freely, Mr. Tronvoll also explained that the Oromo people had expected to rule the country, as one of their own became prime minister and seemed an authentic-enough Oromo: “But then Abiy turned around after six months. Suddenly he was no longer an Oromo. He was an Ethiopianist. And this is what set off the new internal Oromo conflict.”

The intellectualized insult for an Oromo deemed not Oromo enough is ‘assimilated’. This label was also stuck on Abiy Ahmed, who grew up in Oromia, identifies as Oromo, speaks Oromo, but fails the tribal purity test by having an Amhara mother and Amhara wife. And yet, Oromos were certainly no less active than other Ethiopians in mobilizing, when, on November 1, the prime minister called on citizens to prepare themselves to repel the invaders. One recruit was Feyisa Lelisa, an Oromo marathon runner. He had won silver at the 2016 Rio Olympics, where he crossed the finishing line with the “handcuff-me” gesture of crossed wrists over his head, symbolizing the peaceful protests at that time against the TPLF-led regime. Another volunteer was the legendary long-distance runner Haile Gebreselassie. He had previously gone to Tigray to try to mediate and avert war.

My own predictions

On the one-year anniversary of the war, November 3, 2021, the prime minister gave a stirring speech. With a clumsy, literal translation of the various idioms in Amharic, one sentence was rendered in Western media as: “We will sacrifice our blood and bone to bury this enemy and uphold Ethiopia’s dignity and flag”. Mr. Tronvoll’s podcast host, Bjørnar Østby, jumbled this into: “We will bury you in our blood”. Facebook censored it for “inciting violence”. I wrote acerbically about Winston Churchill inciting violence on the beaches. Then again, the social-media giant was not really drawing a line for acceptable language, but reacting to bad publicity. For years, it had been chided for lending its platform to the instigation of murderous ethnic pogroms and mass displacement across Ethiopia. It had to be seen to do something. Compared to monitoring millions of messages in dozens of languages, the cheap option was to remove one high-profile speech.

In late October 2021, just as Ethiopia was in the throes of a near-death experience, the International Crisis Group, a prominent thinktank funded by Western governments, warned of disaster if federal authority continued to weaken. If, however, the federal authority tried to assert itself and its constitutional monopoly on violence, the recommendation was to punish it economically.

Ethiopia retained tariff-free access to the EU market, but some 200,000 poor people, mainly young women, lost their jobs due to Ethiopia being suspended from AGOA, a scheme granting duty-free access to the US market. Of course, this had no effect on the course of the war. Ethiopians were not about to commit collective suicide over lost opportunities for trade. Beyond a harsh yet unenacted US bill, the sanctions and aid cuts were not crippling. They were like a quack doctor slapping the patient in her pain, because she refuses to entrust her survival to his magic spells, preferring to swallow the bitter but tried-and-tested medicine, that is, military mobilization.

“British nationals should leave [Ethiopia] now!” said British Minister for Africa, Vicky Ford on November 24, 2021, along with the other Western governments, who had not only abandoned solidarity with Ethiopia, but also lost confidence in its viability, scaring off foreign investors, tourists, even transit passengers using its hub airport.

However, moving around the capital, I continued to perceive an atmosphere thick with unity and grit. The most knowledgeable commentators, that is, not international pundits but Ethiopians with their fingers on the pulse, were anxious, but definitely not panicking. This brought me to stick my neck out in my first journalistic work on the conflict, “Do-gooders doing bad”, published in Danish and in English on November 11, 2021. Contrary to the consensus of the world press, I stated that the fall of Addis Ababa was “still unlikely”.

A year later, as the Holocaust Museum was putting the world on genocide alert, I assured (on Ethiopian television, no less) that “there won’t be any genocide”. And just when the UN Secretary-General saw the war as “spiraling out of control”, I said: “it looks like the war is over.”

And my mispredictions

But before asking where I got my crystal ball from, consider that only a few months into the war, all my anticipation as regards the crucial geopolitics had been categorically refuted. And yet, I continued to be in denial for at least a year.

Never mind the somewhat simplistic question of ‘who started it’. Part 2 will look at the process of escalation. The moment the parting shots were fired on the night between November 3 and 4, 2020, I predicted, nay blindly assumed, that the West would support those Ethiopians who support the West, that is, those who most subscribe to the current Western ideals. These are supposed to be democracy, human rights and equality, our foundation for settling differences in peace and freedom, to which one might add a market economy, the key to our prosperity. The TPLF had a record of the opposite, namely dictatorship, brutality, chauvinism and statism. Overcoming these scourges had been the promise driving Abiymania. This may have been an overdose of wishful thinking, but at least, as of 2020, substantial headway had been made and amply recognized, as we shall also see in Part 2.

Nobody expected Ethiopia to achieve high standards of rule of law overnight, even less so in wartime. The country’s historical image problem gave credence to the first reports of atrocities committed by members of the Ethiopian National Defense Force (ENDF), and especially by its allies, the Eritrean Defence Forces (EDF), Special Forces under the Amhara regional government, and Fano, a volunteer militia from Amhara. It provoked anger and a sense of dread among Tigrayans. It also sapped Ethiopian morale. Defeating the TPLF insurgency was a popular cause, but, contrary to the single story about tribal rage pushed in international media, to be scrutinized in Part 3, there was no public support for going into Tigray to kill civilians.

Back then, I accepted these stories as the hard truth coming out. I cringed when the prime minister claimed, implausibly, that “not a single civilian has been killed” in the first month of the campaign. The government’s communications were generally abysmal, playing down the human costs, including its own massive losses, but succeeding mainly in coming across as callous and untrustworthy, since everyone knew the country was bleeding and headed for tough times. This hollow triumphalism reflected an old-fashioned military mindset in an era when an honest and empathetic style was sorely needed.

It was encouraging, however, when, in March 2021, the prime minister admitted that war crimes had taken place and promised accountability. And even more so when Ethiopian courts began to indict and sentence its own soldiers for criminal conduct, something unimaginable in previous times, and a healthy sign of expunging an authoritarian legacy. However, as will be clear from Part 3, countless wild accusations against Ethiopia, even from supposedly respectable quarters, have since turned out to be pure disinformation, and so the utmost distrust is warranted. Still, we should all want to know the truth, of course, whatever it is.

Back then, I envisaged that the West would step up support for Ethiopia’s justice system, which had long been awful, but had been showing signs of gradual improvement. It dumbfounded me whenever, throughout 2021, the West wielded sticks instead of carrots. Surely, the priority should be to bolster the federal government’s authority, since weakening it would only push it even deeper into dependence on allies who were less disciplined and largely beyond its control.

By mid-2021, I acknowledged that international media, including some that I had long trusted and treasured, were sensationalizing rather than analyzing. Story-telling works well with dramatic closeups. Zooming out to see the bigger picture was rarely attempted, and when it was, Ethiopian affairs were simplified to absurdity. A galling fixation on the prime minister’s eccentricities substituted for political and historical background. But at least, I thought, serious people were not suggesting it would be better if the TPLF won the war.

Or were they? It became increasingly hard to tell. Discussing who was in the right was almost considered in bad taste. ‘Who cares about petty politics, when our people are getting massacred’, was a TPLF talking point that made an impression.

Then a Zoom meeting was leaked of senior diplomats who both wanted and expected the TPLF to return to power soon. I put this down to individuals whose views had been colored by personal friendship with TPLF leaders, often cultivated during the Obama administration. I kept laboring under the illusion that reality would dawn on the chief Western policy-makers as the rebels closed in on the capital.

Instead, it became a cliché about the conflict that “there are no good guys”, when really it ought to have been about good and bad outcomes. Any analyst worth his salt, I reasoned, knew that the TPLF and OLA had no prospect of ruling in peace. In fact, Kjetil Tronvoll made no bones about it.

Mr. Tronvoll said: “If Addis falls, the war will go on. There won’t be peace because you take Addis”. Indeed, he foresaw that it would open up new, destabilizing fronts: “The war, or the wars, will carry on in new phases and with new intensities.” This was spot on. The many ensuing wars between militias of ethnic statelets with undefined borders would have been as intense as during the breakup of Yugoslavia, but with five times the population, four times the territory, ten times the number of ethnicities. Mr. Tronvoll seemed upbeat about this, but the West as a whole did not want to deal with 120 million refugees. Right?

Surely not. And while the initial optics, just glancing at the map, were of the Ethiopian behemoth swatting the Tigrayan minnow, by now the international community could see that the TPLF rebellion was truly an existential threat. Right?

Preaching to the savages

Well, rather than coming to grips with Ethiopian politics, influential Westerners assumed a stereotype of the African tribal war that civilized beings should not take sides in, but wag their fingers at.

With exemplary neutrality, the EU opposed both the attack on the capital and the defense against the attack on the capital. Four months later, Mr. Borrell would sing to a very different tune on the war in Ukraine.

“It’s time to put our weapons down. This war between angry, belligerent men – victimizing women and children – has to stop,” said Linda Thomas-Greenfield, US Ambassador to the UN, demanding “negotiations without preconditions”, just when the TPLF was as close to the capital as it would ever get.

The old adage of peace through strength is only for rich countries, went the logic. A poor one must make do with peace through power-sharing with its strongest warlords. The predominance of aid officials in charge of relations with Ethiopia gave the impression that, rather than using aid in pursuit of foreign-policy principles, foreign policy was being used in pursuit of aid principles. This may sound altruistic, but it is really just condescending, born of a sense of pity and charity rather than solidarity and shared interest. Thus, in order to guide development cooperation, there is an elaborate ‘peacebuilding framework’ in place under UN auspices. It generalizes about conflicts in poor countries being caused by resource scarcity and intercommunal animosity. These primitive motives contrast with how rich countries will invoke some high ideals for their own resort to violence. Top of that list is usually democratic legitimacy. But Edward Hunt, writing in The Progressive Magazine on November 18, 2021, had no time for that, and actually criticized the Biden Administration for wanting “to prevent the overthrow of the embattled Ethiopian prime minister, whom they see as the key to strengthening U.S. power in the region”. Mr. Hunt classified the TPLF as leftist, that is, like himself, and held that, rather than having humanitarian concerns, “what they [the US government] really fear is that the rebels will seize power and reverse the neoliberal and [pro-American] geopolitical agenda of Abiy”. This is interesting, because most Ethiopians had the opposite view of the American role. By then, their overwhelming perception, right or wrong, was that the number one superpower was not just neutral, but actively sponsoring the TPLF.

Keen to dispel this, President Biden’s then-Special Envoy, career diplomat Jeffrey Feltman, held a press briefing in Addis Ababa on November 23, 2021. He was mistaken to rule out Ethiopia solving the problem militarily, but no, he was not crazy. Rather than entertaining regime change, he acknowledged the unconscionable danger of Ethiopia “unraveling”. He said the TPLF had invaded Amhara and Afar, and ought to withdraw to Tigray. He understood that the Ethiopian view had been shaped by a long history of oppression under the TPLF, and observed that Addis Ababa would react “with unrelenting hostility” to a TPLF takeover, referring to such an event as “a bloodbath situation”. Most importantly, he accepted the democratic legitimacy of Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed and his government: “Whatever the imperfections are in the elections, I think that they, in general, his premiership reflects a popular mandate that we recognize”. And yet, he said over and over: “we are not taking sides here”.

My model of reality upended

This made it official. The US was not taking the side of a fledgling democracy against those out to commit a bloodbath in its capital. And the main Western opinion formers did not even remark on it. At the UN Security Council, the US tried to have Ethiopia censured, because “it has publicly called for the mobilization of militia”. Russia and China came to Ethiopia’s rescue, so WHO’s Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus changed overnight from friend to foe of China.

The world had turned upside down! I pinched myself. Ouch. No, I had not entered an alternate reality. I had erred in my model of reality.

By the end of December 2021, it was clear that, hypothetically speaking, had Ethiopia refrained from mobilizing, as The Economist and the West more generally demanded, and even if negotiations from such a position of weakness had, against all odds, succeeded in freezing the frontline rather than ending in that “bloodbath situation” inside the capital, then millions in Afar and Amhara would still be displaced, living or dying under a nightmarish occupation. It has now been proved that the path to end this war was what Ethiopia did instead. And yet, Ethiopia is still waiting for an apology from all these trend-setting news outlets and powerful nations.

The concluding Part 4 will discuss why the geopolitics of the conflict played out the way it did, and what historical, ideological and psychological factors blocked our understanding of Ethiopians in the same way that we Westerners understand ourselves, that is, as reluctant yet principled users of armed force. Suffice to note here that, if someone had told me before the war, or even several months into the war, that in an imminent bust-up between Ethiopia and the West, I would basically take Ethiopia’s side, I would have scoffed and said: “get real!” I could have seen myself ending up on the opposite side of Alex de Waal and Kjetil Tronvoll, given their closeness to the TPLF, but never ever imagined that their perspective would get nearly all the talking time, whereas mine would be relegated to the fringe.

I continue to believe that a home-grown democracy along with the old-school definitions of human rights and equality are universal values. Violence against the state can be justified only as a very last resort to achieve these ends. My ideals have not changed. But my worldview has been shattered. Putting it back together remains a work-in-progress, though one conclusion is clear: the Western narrative about the war in Ethiopia says a lot more about the West than it does about the war in Ethiopia.

But before digging deeper into this, it helps to have a clearer idea of what the war was about and not about.

PART 2: CAUSES OF THE WAR

Dumbed down by the New York Times

What were the issues underlying the war? First, let’s take a look at what became conventional wisdom in newsrooms.

Across the globe, American cultural influences dwarf knowledge of Ethiopia. It is not just Hollywood. The New York Times has particular brand value, and its articles are routinely translated into many languages. This is how, in December 2021, its Africa correspondent, the young Irishman Declan Walsh, having already scripted a David-and-Goliath-themed war romance, starring himself as the intrepid reporter from inside the camp of the plucky rebels, cooked up a backstory to match, which has infected pop journalism ever since, like some awful Disney-movie adaptation of real history.

It goes like this: “It was a war of choice for Mr. Abiy”, who plunged his country into it because he felt “emboldened”. Why? Because he had received the Nobel Peace Prize in late 2019. Those who did not tune into the grand ceremony in Oslo live have seen the video clips, so this has got to be factored into the cause of the war. And not only those gullible Nobel Committee members, but the West in general “got this leader spectacularly wrong”, since “the peace deal” that Abiy Ahmed struck in 2018 with Isaias Afeworki, the authoritarian leader of Eritrea, was really a sinister pact for these two “to secretly plot a course for war against their mutual foes in Tigray”.

Naming one disaffected government official as his source, this affirmation is based on testimonies of prior preparations and purges: “New evidence shows that Ethiopia’s prime minister, Abiy Ahmed, had been planning a military campaign in the northern Tigray region for months before the war erupted one year ago”, writes Mr. Walsh.

Really, only for months? More like for years!

Abiy Ahmed emphatically did not come to power in 2018 by promising war. But the old guard responded to his reforms with saber-rattling from the get-go. It took less than three months for the first attempt to assassinate him. We shall soon see how the TPLF refused to let go of its control of the military. So how could the prime minister not be planning for the eventuality of war? He was also sending delegations to Tigray to try to negotiate. If anything, he could be criticized for insufficient planning, given the massive losses of his forces during the initial clashes. The purging of the army was a delicate but vital task, which had been proceeding in the public view.

Nor was Mr. Walsh the first to observe that the new-found warm relations between Ethiopia and Eritrea were driven by the TPLF being a common enemy. This was the headline of Bronwyn Bruton’s aforementioned prescient article published fully two and a half years before the war. In 2019, Ann Fitz-Gerald had mapped out the growing threat to national security from regional militias, proposing urgent measures to defuse the tension between the federal and the Tigray regional government. People with firsthand knowledge of Tigrayan politics warned, as early as 2018, sometimes even in English, that the TPLF was mobilizing for war, and that it was framing the purges of its loyalists from the security apparatus, and of its agents of corruption from the economy, as “ethnic-based attacks”.

Declan Walsh’s brief is to cover the vast continent of Africa. He could not be expected to specialize in 54 different countries, but he should have had the humility to study some of the vast public record of social, economic, political and military developments that led to war in Ethiopia. Having no patience for the complexity of a true story, he went for freestyle psychoanalysis to build a villainous character for a cinematic drama, which, alas, captured the popular imagination much better than the serious scholarship, probably because it plays up the role of the West, and also fits the stereotype about the African war as a purely emotional affair ignited by big men on a whim.

Small wonder Mr. Walsh is constantly taken aback by events. After the TPLF’s march on the capital was repelled, he wrote of “a stunning reversal”. He gave short shrift to the explanation obvious to those of us who had believed in the eventual failure of the TPLF’s march on the capital, namely the high morale of soldiers in a country pulling together to face down an existential threat. Instead, he put it down to other countries’ determination to keep the bad guy in power by supplying him with combat drones, even though this trade had been written about since the beginning of hostilities. He also assumed Ethiopian arms purchases to be inimical to conflict settlement, although, quite predictably, they ended up shortening the war. After the peace deal was signed, he tweeted that it was “a huge surprise”, though it was not so for Ethiopians or even for lesser known Western journalists, like Alastair Thompson.

Two and a half years of escalation

In contrast to Declan Walsh, Kjetil Tronvoll has followed Ethiopian politics for years. He is not a great forecaster, as when he expounded on how the AU-led peace process was doomed to fail two weeks before it succeeded. But in that same interview, he was correct in stating that the buildup was gradual. Though no shots were fired when Abiy Ahmed took office, Mr. Tronvoll had a point when he suggested that this was when the conflict was set in train. He was also not far off in placing the origin story of the war as the end of the reign of Prime Minister Meles Zenawi, the TPLF strongman who passed away from disease in 2012, aged 57. Pro-TPLF Ethiopians, including many a self-proclaimed human-rights advocate, see him as a visionary father figure, while anti-TPLF Ethiopians mostly remember him as a tyrant, who enriched himself, his wife and his clique, put ethnicity on ID cards, played ethnic groups up against each other, and ruled through force and fear. Adding nuance, a stable dictatorship can feel safer to live in, and throughout Ethiopia, far beyond the TPLF heartland, Meles nostalgia is not uncommon. His tomb remains well guarded in the holiest of places of Ethiopian Orthodox Christianity in Addis Ababa.

One could also date the first escalatory step to the election held on May 15, 2005, when an almost free and fair campaign descended into a vicious crackdown after Meles Zenawi clearly lost. It was at that point that Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus joined the cabinet, first as Minister of Health.

Tedros back in the days, flanked by the TPLF power couple Azeb Mesfin and Meles Zenawi.

In 2006, a judiciary inquiry led by senior Ethiopian judges documented summary executions of teenagers who had protested the election fraud. Needless to say, the investigators went into exile on the eve of publishing their report.

The leader of the 2005 EU Election Observation Mission, a Portuguese named Ana Gomes, is still an esteemed figure in Ethiopia.

There were harsh words of condemnation from Western capitals and a few months’ lull in the increase in aid budgets. Then it was back to business as usual. If we insist on centering the role of the West, it did incur some blame by cozying up to the TPLF-dominated regime for those 27 years from 1991 to 2018. The lesser evil, the devil you know, all such excuses have validity. After all, many Ethiopians also collaborated with the regime, or worked to change it from the inside, which is what would pave the way for Abiy Ahmed’s takeover. Moreover, international isolation is rarely helpful.

There were embarrassing excesses, however, particularly under the presidency of Barack Obama, who said, in 2015, that the government of Ethiopia had been “democratically elected”. In 2012, the American then-Ambassador to the UN, Susan Rice, eulogized Meles Zenawi at his funeral, calling him “a true friend to me”. Whatever Ms. Rice’s role in US policy on this war, her presence in the Biden administration became a source of Ethiopian distrust.

Nevertheless, it is easy to overstate Western power, whether it be denounced as the problem or promoted as the solution. Ethiopian politics is conducted mainly by Ethiopians in Ethiopia. Accordingly, here are the actual political flashpoints as reported in Ethiopia, by and for Ethiopians, prior to the war.

Not everyone was an Abiymaniac

Certainty that the war was coming, more than a year before it did, was expressed by Sebhat Nega, cofounder and grand old ideologue of the TPLF, who led a purge in the military as late as February 2018, just before Abiy Ahmed took over. In an interview with the BBC in Amharic on October 17, 2019, he said: “It’s clear that we are headed for civil war”, adding that there would be “carnage within and between the regions”.

This raised some eyebrows, but nothing more than that. It was at the point of peak Abiymania. Only six days before, Abiy Ahmed’s Nobel Peace Prize had been announced. One month earlier, the prime minister had invited the public to see the inside of the infamous Maekelawi Prison, whose torture dungeons had featured in a documentary shown on Ethiopian television, recounting what happened there to regime opponents, from sodomy to amputation of limbs. The prime minister joined the first group of visitors, flanked by ordinary Ethiopians and Supreme Court President Meaza Ashenafi, who had recently been appointed for her distinguished career in the field of human and women’s rights. Former political prisoner Daniel Bekele was also present. He had just become the head of the Ethiopian Human Rights Commission. He praised the government for closing this detention facility, yet also complained about a continuing lack of due process, highlighting that democratizing Ethiopia was an ongoing challenge. He has kept up his critical stance towards the government ever since.

These new establishment figures were illegitimate, according to Sebhat Nega, who is commonly referred to by his adversaries as the “godfather of the TPLF”. He used the BBC interview to accuse the USA, under the Trump administration, of masterminding “coups” in plural, first by bringing Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed to power on the national stage in April 2018, and then by ridding some regions of TPLF-loyal governors. The most notorious case was in the Somali Region (not the country of Somalia, but Ethiopia’s arid east with mostly Somali-speaking people). Despite Governor Abdi Illey’s belated conversion to Abiymania, he was deposed and arrested in August 2018, after it was revealed that he had housed wild animals together with political prisoners. His defense was that he was just a pawn of the TPLF’s man, Getachew Assefa, once a powerful torturer-in-chief, who was described by one Ethiopian journalist as: “de facto leader of the nation since the death of Meles Zenawi in 2012”. This was probably an exaggeration, but Getachew Assefa was undoubtedly a menace to the transition of power. He was fired as Intelligence Director as early as June 2018. He took as many secrets and assets as possible with him to Tigray, where he was shielded from arrest by the TPLF-led regional government. He became a suspect in the aforementioned attempt on the prime minister’s life, when a bomb blew up at a public event on June 23, killing two and injuring some 150 people. Then he was wanted for instigating ethnic pogroms around the country, not to speak of his horrendous human-rights violations during the TPLF’s heydays. However, rather than handing him over to federal prosecutors, on October 1, 2018, the TPLF reelected him to its Executive Committee. It was reported that he died from illness in March 2021.

Sebhat Nega’s BBC interview also took place in the dying days of the long-ruling Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front, EPRDF, a coalition of ethnically-based parties, which was dissolved on December 1, 2019 and replaced by the Prosperity Party, a single outfit for all ethnicities, albeit divided into regional branches. The TPLF was invited to join, but declined. The ruling-party name change — do notice how ‘revolutionary front’ turned into ‘prosperity’ — chimed in with a drive to replace militaristic statism with economic liberalism. At the World Economic Forum in 2019, the annual shindig for globalized capitalism in Davos, Switzerland, Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed was the toast of the town, buzzing about “vibrant democracy” and “opening up the economy”. It was a radical break with EPRDF ideology.

The EPRDF had been founded in 1988 on the TPLF’s initiative as a vehicle of power, which it assumed in 1991, after winning a long guerrilla war under the leadership of Meles Zenawi. When Meles passed away in 2012, Hailemariam Desalegn was installed as prime minister. He came from a small ethnic group, the Wolayta, and was widely considered a puppet of the TPLF powers-that-be ensconced in the security apparatus. Popular protests and regime crackdowns intensified in a vicious cycle that was finally broken in March 2018, when Mr. Hailemariam mutinied simply by resigning. At this point, Abiy Ahmed became the new EPRDF leader with support from EPRDF-affiliated members of parliament from every region, except Tigray.

It was not obvious that he would become a reformer. Sebhat Nega may even have had some hopes for the new national leader, who, interestingly, started out in politics as a 14-year-old child soldier in the TPLF army. This is how he became fluent in Tigrinya, the language of Tigray, which served him well in his career as head of the regime’s cybersecurity.

However, Abiy Ahmed presented a vision for the country that differed from the TPLF’s. He started off by asking forgiveness for past oppression, releasing thousands of political prisoners and inviting exiled politicians back home for dialogue. In contrast to the male-dominated culture of the TPLF, he appointed women, not just to the ceremonial presidency, but also to the most powerful positions in the cabinet, to preside over the Supreme Court, and as chairwoman of the National Election Board. Within a year, Ethiopians enjoyed unprecedented press freedom.

All this was music to the ears of the Ethiopian masses, and to Western media and governments too. What the international community failed to hear was the background grumbling of the old guard. On June 12 and 13, 2018, the TPLF held an emergency meeting in Mekelle, the capital of Tigray, to address the two latest policy measures that had provoked their ire: implementation of an old peace deal with neighboring Eritrea and privatization of state corporations.

Obstructing peace with Eritrea